(Before you ask, the title comes from a Misfits bootleg and the bootlegger responsible says: "One of the worst release[s] in regards of artistic merit...was my absolute biggest seller: The Misfits' If You Don't Know The Song... - I didn't know the names of the songs, that's why I called the album that. - Heylin, 2003)

In an age where practically anything and everything can be downloaded onto your computer with little to no effort being exerted, we are already losing the thrill and exoticism of encountering bootleg records in the wild.

A bootleg LP, CD or tape is

defined as being a collection of rare and unreleased material issued without

the artist’s consent. Your average

illegal platter would normally consist of studio outtakes (normally let out

into the wild via someone working inside a recording studio, an individual that

was handed this stuff via the musician directly or an associate, and in rare

circumstances a benevolent artist themselves) or a live recording (either taped

by an audience member from their seat or via connections from the mixing

desk). Depending on the source material

or the production quality, the results could end up being a mixed bag and you

may often get stung when you eventually purchase it – well, you can hardly go

and complain to Trading Standards can you?

A bootleg LP, CD or tape is

defined as being a collection of rare and unreleased material issued without

the artist’s consent. Your average

illegal platter would normally consist of studio outtakes (normally let out

into the wild via someone working inside a recording studio, an individual that

was handed this stuff via the musician directly or an associate, and in rare

circumstances a benevolent artist themselves) or a live recording (either taped

by an audience member from their seat or via connections from the mixing

desk). Depending on the source material

or the production quality, the results could end up being a mixed bag and you

may often get stung when you eventually purchase it – well, you can hardly go

and complain to Trading Standards can you? Before we go any further:

bootlegging is not the same as piracy.

Bootlegging is based around unreleased material. Piracy is just a simple case of copying what

is already legally out there, as anyone in my age group can attest to if you’ve

seen those shoddy tapes at local market stalls during the 80s and 90s, courtesy

the Saudi Arabian 747 cassette label. You're not missing out on these ones, these tapes were truly cat shit and often featured missing songs, censorship (eg. DAF's 'Der Mussolini' being shortened to 'Der' on a compilation) and other songs pulled from other albums, with crackles, record skips an' all. A friend's dad had a cupboard full of these things, but I wouldn't be proud to show off a stash like this. There would be a much more positive response if you pulled out a load of used syringes and blackened spoons instead.

Before we go any further:

bootlegging is not the same as piracy.

Bootlegging is based around unreleased material. Piracy is just a simple case of copying what

is already legally out there, as anyone in my age group can attest to if you’ve

seen those shoddy tapes at local market stalls during the 80s and 90s, courtesy

the Saudi Arabian 747 cassette label. You're not missing out on these ones, these tapes were truly cat shit and often featured missing songs, censorship (eg. DAF's 'Der Mussolini' being shortened to 'Der' on a compilation) and other songs pulled from other albums, with crackles, record skips an' all. A friend's dad had a cupboard full of these things, but I wouldn't be proud to show off a stash like this. There would be a much more positive response if you pulled out a load of used syringes and blackened spoons instead. For a more in-depth look at this whole phenomena (as well a handy way of compiling a shopping list), I would strongly suggest purchasing Clinton Heylin’s thorough and entertaining book Bootleg! The Rise & Fall Of The Secret Recording Industry (Omnibus Press, 2003) for a more insightful overview, replete with juicy anecdotes from the people behind these artistic labours and the major events that unfolded. For the purpose of this article, I am merely going to tell my own story with a personal combination of favouritism and some dice.

You never forget your first

encounter with a bootleg LP (or CD). For

me, it was trawling through the Ipswich Record & Tape Exchange, a small

poky and smelly shop located in a then-crumbling and partially vacant area of

the town centre. Ever since I was given

my first shonky little record player at age 7, I needed vinyl to play on

it. As a result I gravitated to this

shop, buying up stuff I would later regret for pennies before common sense,

growing up and developing your own taste became prevalent (eg. 50p for a bag of

50 singles straight from Radio Orwell’s bins).

One day, I walked in to see them riskily selling some down and dirty

bootleg vinyl on the wall and it was pretty pricey. Madam

Stan by Adam & The Ants was the one that caught my eye: homemade with

track listings written in fake Italian on the label, I scooped up what money I

had and it was mine. I knew that it was

a risky purchase as it could turn out to be a load of unlistenable codswallop,

but I loved the illicitness and the forbidden fruit nature as well being an

Adam Ant fan.

You never forget your first

encounter with a bootleg LP (or CD). For

me, it was trawling through the Ipswich Record & Tape Exchange, a small

poky and smelly shop located in a then-crumbling and partially vacant area of

the town centre. Ever since I was given

my first shonky little record player at age 7, I needed vinyl to play on

it. As a result I gravitated to this

shop, buying up stuff I would later regret for pennies before common sense,

growing up and developing your own taste became prevalent (eg. 50p for a bag of

50 singles straight from Radio Orwell’s bins).

One day, I walked in to see them riskily selling some down and dirty

bootleg vinyl on the wall and it was pretty pricey. Madam

Stan by Adam & The Ants was the one that caught my eye: homemade with

track listings written in fake Italian on the label, I scooped up what money I

had and it was mine. I knew that it was

a risky purchase as it could turn out to be a load of unlistenable codswallop,

but I loved the illicitness and the forbidden fruit nature as well being an

Adam Ant fan. When I got home, I placed it on

the turntable. I was pleasantly

surprised. There were familiar tracks

such as 'Physical (You’re So)' and 'Friends' but these were all considerably

different versions, all recorded by the spiky post-punkers responsible for Dirk

Wears White Sox, not the chart-topping swashbucklers soon to come. There were even songs I never knew existed

such as 'Boil In The Bag Man', 'Rubber People' and 'Bathroom Function', and the

LP seemed to come from demos recorded in between their tenure at Decca and the

aforementioned album that didn’t surface until a year later. Best of all, the sound quality was excellent

throughout. This was definitely a

surprise to me. Needless to say, I

bolted straight back to the shop next Saturday to snatch that Stranglers

bootleg, but either someone else had bought it or they decided not to risk it

and took it off the shelves.

When I got home, I placed it on

the turntable. I was pleasantly

surprised. There were familiar tracks

such as 'Physical (You’re So)' and 'Friends' but these were all considerably

different versions, all recorded by the spiky post-punkers responsible for Dirk

Wears White Sox, not the chart-topping swashbucklers soon to come. There were even songs I never knew existed

such as 'Boil In The Bag Man', 'Rubber People' and 'Bathroom Function', and the

LP seemed to come from demos recorded in between their tenure at Decca and the

aforementioned album that didn’t surface until a year later. Best of all, the sound quality was excellent

throughout. This was definitely a

surprise to me. Needless to say, I

bolted straight back to the shop next Saturday to snatch that Stranglers

bootleg, but either someone else had bought it or they decided not to risk it

and took it off the shelves.Cut to a few years later, I was doing voluntary work for a local company, which had its own in-house radio station (yes, yours truly had a show there for a number of years). Bruce, the boss of the organisation (and former member of noise-rockers Tender Lugers and Earth Mother Fucker) tolerated my new found love for obscure post-punk and he introduced me to a number of bands and artists that I only had a passing knowledge of. He let me borrow his exhaustive collection of original Stooges vinyl (including the death throes encapsulated on the 1974 live offering Metallic K.O.) as well as his well-worn copy of MC5’s Back In The USA. Having also discovered the majesty of The Velvet Underground at around the same time, he lent me his horde of Velvets bootlegs too. I didn’t have to beg because once I gave back the current trove of goodies, these mysterious bootlegs were now mine to hear too.

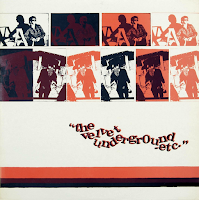

First on the turntable were two late 70s bootlegs originating from Australia, Etc. plus And So On. What a revelation! The first side of Etc. was devoted entirely to a pre-VU Lou Reed’s tenure at the cheap and cheerful Pickwick International, cutting cash-in ditties such as 'Cycle Annie' and 'The Ostrich'. Not only were they fascinating, they were also really good, especially 'The Ostrich'. There were also rare outtakes such as 'Foggy Notion' which, although it sounded cruddier, sounded more authentic than the horrid 80s remix on my Peel Slowly And See CD boxset. There were also the some 1969-era live cuts and a couple of John Cale solo experiments that were quite tough on my teenage ears.

Next up was the jewel in the crown: Sweet Sister Ray. Described in Heylin’s book as “perhaps the most avant-garde vinyl statement ever made on behalf of the Velvets”, the double album is a hymn of praise to 'Sister Ray', the final cut on their White Light/White Heat platter which still sounds incredibly powerful, demolishing and ear-splitting after 50 years. Sweet Sister Ray consists of the 40-minute title track followed by two separate performances of “Sister Ray” by the Doug Yule line-up.

Recorded live in April 1968 shortly before Cale was asked to leave, 'Sweet Sister Ray' is a 40-minute meditative preamble which has an almost ethereal folky atmosphere to it before Lou “I’m sorry I was a cunt to you but I am on a diet of wheat husks” Reed stomps on the distortion box to let some holy feedback consume itself before punctuating the organ-dominated swirl with sharp intermittent barks. The nearest comparison point to this track is Fred Frith’s 'No Birds' from the free-form yet magical Guitar Solos album from 1974. Both tracks are in the same key of C and maintain the same manifesto: improvisation isn’t the name of the game but conjuring an atmosphere and a presence is the primary reason for being.

Onto LP 2 and the previously described run throughs of 'Sister Ray'. Side 3 is not as aggressive or attention grabbing as you would expect but still has an insistent and borderline swing to it. If you want assorted electronic shrieks and howls, Side 4 is the place to go. Taken from a source known as the 'guitar amp tape’ because it’s dominated by Lou’s guitar to the detriment of everything else, it is still a wonderful righteous howl. No legitimate record company would ever dare to put this stuff out, but you’ve got to hand it to the bootleggers to throw some interesting and compelling stuff out there. From hereon in, I picked up a copy of Heylin’s book and made a note of what seemed like the most interesting platters to track down.

I was a late comer to Bob Dylan’s

material, in fact so late to the party was I that my first encounter with the

infamous electric set recorded in Manchester '66 came via its legitimate release

(and what a violent corker it was). From

that point on I preferred my Dylan output from the speed-addled pissed off

little sod of the 1966 tour up to the Basement Tapes period of 1968. The latter was documented perfectly on A Tree With Roots, a 5CD collection of

basement tape material and featured the much superior original versions of 'Open

The Door Homer', 'Odds & Ends' and 'Billion Dollar Bash' in all their rough

and ragged glory, as opposed to the Robbie Robertson botch job compilation from

1975. There were also a lot more folk

and country covers such as 'That Auld Triangle' (aka 'The Banks Of The Royal

Canal'), but this set has finally been given a proper release with much more

pleasing sonic improvements to tapes that were never intended to be put out in

the first place.

I was a late comer to Bob Dylan’s

material, in fact so late to the party was I that my first encounter with the

infamous electric set recorded in Manchester '66 came via its legitimate release

(and what a violent corker it was). From

that point on I preferred my Dylan output from the speed-addled pissed off

little sod of the 1966 tour up to the Basement Tapes period of 1968. The latter was documented perfectly on A Tree With Roots, a 5CD collection of

basement tape material and featured the much superior original versions of 'Open

The Door Homer', 'Odds & Ends' and 'Billion Dollar Bash' in all their rough

and ragged glory, as opposed to the Robbie Robertson botch job compilation from

1975. There were also a lot more folk

and country covers such as 'That Auld Triangle' (aka 'The Banks Of The Royal

Canal'), but this set has finally been given a proper release with much more

pleasing sonic improvements to tapes that were never intended to be put out in

the first place. The rejected version of Blood On The Tracks (Blood On The Tapes) was much more a slow

burner for me. Although roughly half of

this material made it onto the album, Bob’s brother decided that the other half

was far too repetitive and monotonous, twisting his brother’s arm into re-recording

most of it. Luckily for us an acetate of

the aborted New York sessions got out there and was duly bootlegged. Having heard the official release and being

left cold, the acetate was a work of beauty.

Yes, most of the tracks are in the same key, but that it is not a

minus. If anything, the original

sessions have more of a spark and confidentiality that really tugs on your

heart strings. As with A Tree With Roots, the complete Tracks sessions have since been

released, with the acetate track listing eventually seeing an official release

in time for this year’s Record Store Day event.

The rejected version of Blood On The Tracks (Blood On The Tapes) was much more a slow

burner for me. Although roughly half of

this material made it onto the album, Bob’s brother decided that the other half

was far too repetitive and monotonous, twisting his brother’s arm into re-recording

most of it. Luckily for us an acetate of

the aborted New York sessions got out there and was duly bootlegged. Having heard the official release and being

left cold, the acetate was a work of beauty.

Yes, most of the tracks are in the same key, but that it is not a

minus. If anything, the original

sessions have more of a spark and confidentiality that really tugs on your

heart strings. As with A Tree With Roots, the complete Tracks sessions have since been

released, with the acetate track listing eventually seeing an official release

in time for this year’s Record Store Day event.

A chapter in Bootleg! Covered the nefarious and godlike activities of Richard,

whose finest work toed dangerously close to piracy, but these were not the Dictaphone-pointed-at-an-Edison-photograph

scams of the 747 variety, this was Wild Geese-style rescue shit. First on the block is Michigan Nuggets (aka Michigan

Brand Nuggets). Featuring a

mocked-up cereal box featuring Iggy Pop on the cover (but not amongst the track

listing), this double LP set scoops some of the finest 7” jewels unleashed

between 1966-1970 by the likes of Bob Seger & The Last Heard, The

Rationals, Terry Knight & The Pack and MC5.

It’s pretty hectic non-stop fuzzed up bangers, although they could have

included 'Mona' by The Iguanas (featuring Iggy) in place of 'The Ballad Of The Yellow

Beret'.

It's because of Michigan Nuggets, my wife became a devout

fan of Bob Seger’s flawless streak of late 60s stripy-shirt garage stompers,

thankfully unaware of his overall career of mellow brunch jams. In fact, my wife could easily write her own

piece on all these grey-area psych and garage comps, as she owns an enviable

amount of them (The Pebbles Box, Girls In

The Garage) as well as three instalments of Las Vegas Grind.

It's because of Michigan Nuggets, my wife became a devout

fan of Bob Seger’s flawless streak of late 60s stripy-shirt garage stompers,

thankfully unaware of his overall career of mellow brunch jams. In fact, my wife could easily write her own

piece on all these grey-area psych and garage comps, as she owns an enviable

amount of them (The Pebbles Box, Girls In

The Garage) as well as three instalments of Las Vegas Grind.

It's because of Michigan Nuggets, my wife became a devout

fan of Bob Seger’s flawless streak of late 60s stripy-shirt garage stompers,

thankfully unaware of his overall career of mellow brunch jams. In fact, my wife could easily write her own

piece on all these grey-area psych and garage comps, as she owns an enviable

amount of them (The Pebbles Box, Girls In

The Garage) as well as three instalments of Las Vegas Grind.

It's because of Michigan Nuggets, my wife became a devout

fan of Bob Seger’s flawless streak of late 60s stripy-shirt garage stompers,

thankfully unaware of his overall career of mellow brunch jams. In fact, my wife could easily write her own

piece on all these grey-area psych and garage comps, as she owns an enviable

amount of them (The Pebbles Box, Girls In

The Garage) as well as three instalments of Las Vegas Grind. Back to Richard, he was also responsible for the infamous 10LP Dylan box Ten Of Swords (released before CBS' Biograph box and causing massive shitfits upon its circulation) and Tis The Season To Be Jelly, a live recording of Zappa & The Mothers from 1967 before he started writing unfunny shit accompanied by marimbas. Just as infamously, he was also the

mastermind behind the hysterical Elvis’

Greatest Shit. Gathering together

the deposed King’s worst songs ('Yoga Is As Yoga Does', 'Ito Eats' and 'There’s

No Room To Rhumba In A Sports Car') and wrapped up in an incredibly vicious

cover (click on the image nearby for more detail) and a prescription allegedly

scribbled by Elvis’ personal doctor. As

someone who only ventured as far as Mr P’s Sun sessions, I can totally applaud

this compilation and it withstands repeated listens. To paraphrase Richard himself in the book,

Elvis collectors found the album so distasteful yet had to own a copy to

complete their collection.

Back to Richard, he was also responsible for the infamous 10LP Dylan box Ten Of Swords (released before CBS' Biograph box and causing massive shitfits upon its circulation) and Tis The Season To Be Jelly, a live recording of Zappa & The Mothers from 1967 before he started writing unfunny shit accompanied by marimbas. Just as infamously, he was also the

mastermind behind the hysterical Elvis’

Greatest Shit. Gathering together

the deposed King’s worst songs ('Yoga Is As Yoga Does', 'Ito Eats' and 'There’s

No Room To Rhumba In A Sports Car') and wrapped up in an incredibly vicious

cover (click on the image nearby for more detail) and a prescription allegedly

scribbled by Elvis’ personal doctor. As

someone who only ventured as far as Mr P’s Sun sessions, I can totally applaud

this compilation and it withstands repeated listens. To paraphrase Richard himself in the book,

Elvis collectors found the album so distasteful yet had to own a copy to

complete their collection.Television’s Double Exposure is another release that we should all be thankful for. It combines the rare Eno demos cut with the Richard Hell line-up, replete with that oh-so-familiar bouncy bass work that belongs to the Blank Generation, plus a few cuts from Terry Ork's apartment (exit Richard, enter pock-marked Fred Smith on bass duties) perfecting that Television precision on the same tape that the awe-inspiring 'Little Johnny Jewel' single may have sprung forth from.

Finally, as I cannot think of a good way to round up this piece, I have to highly recommend the thoroughly dubious and illegal-right-from-the-start Spanish LP Los Exitos De Sex Pistols por Los Punk Rockers. The story goes that a Spanish record label were too cheap to license Never Mind The Bollocks by The Sex Pistols for general release in Post-Franco Spain, so they simply corralled a local band (who may or may not have the horrific prog band Asfalto) to re-record it in what sounds like a lathe cut on one of those Russian x-ray flexidiscs. As far as I can remember, the official record itself did not come with a lyric sheet so the leader of Los Punk Rockers gives it a shot, with as much of an approximation of snotty nosed Lydon-isms as much as possible. As writer Taylor Parkes remarked on an episode of the Chart Music podcast, the vocalist obviously knows a little bit of English as words appear that didn’t appear on the Sex Pistols record, as well as sounding like the Great Cornholio from Beavis & Butthead. Needless to say the results are pretty much indescribable and the album is quite easy to find on things like Soulseek and it may have to stay this way as there’s pretty much no chance of this ever getting an official release. Then again, you have to wonder whether Los Exitos De Sex Pistols Por Los Punk Rockers was ever legitimate to begin with.

In summary, bootlegs were grand

and it is always a pleasure to uncover unheard gems that the artist in question

would undoubtedly nix if the subject of an official release comes up. There have been a number of examples (eg. any

Macca reissue) where the artist responsible has their own bizarre and dubious

ideas about what should and shouldn’t be unleashed. This does not mean that anything consigned to

the vault is automatically great (Van Morrison’s The Contract Breaking Sessions being another example), but there is

always something out there that will be of interest to die-hard fans. Some fans may be content to simply own a

greatest hits package or the albums meant for general release, but others want

to explore further. If it’s a musician

or band that you love you’ll hopefully have no problem uncovering tape after

tape of raucous live shows or studio throwaways.

In summary, bootlegs were grand

and it is always a pleasure to uncover unheard gems that the artist in question

would undoubtedly nix if the subject of an official release comes up. There have been a number of examples (eg. any

Macca reissue) where the artist responsible has their own bizarre and dubious

ideas about what should and shouldn’t be unleashed. This does not mean that anything consigned to

the vault is automatically great (Van Morrison’s The Contract Breaking Sessions being another example), but there is

always something out there that will be of interest to die-hard fans. Some fans may be content to simply own a

greatest hits package or the albums meant for general release, but others want

to explore further. If it’s a musician

or band that you love you’ll hopefully have no problem uncovering tape after

tape of raucous live shows or studio throwaways.I love the fact that I have the complete 35-minute version of Can’s 'Doko E' (of which only roughly a minute is out there in remastered form) or that I can throw a rock anywhere and hit an excellent live soundboard recording by the Miles Davis Ensemble circa 1965-1975. As a Stooges fan, there are countless grey-area releases and outright bootlegs in varying quality – I am a sucker for rare live recordings where you can practically feel the tension in the room and the sound of Iggy literally spitting teeth, or perhaps crooning 'The Shadow Of Your Smile' before launching into 'New York Pussy Smells Like Dog Shit' (Easy Action released this 1971 audience tape, so go listen for proof). They may not have been perfect but if you’re not fussed about the packaging and only care about the contents, most of this is easy to find in the right places and at least you don’t have to pay extortionate prices for something which may or may not be cat shit.

Finally, here’s a short film from 1971 highlighting the bootleg phenomenon in its early days. The morals of this story are: Yoko is the only one who’s got it right and don’t fuck with Peter Grant. Also keep an eye out for Rick Wright’s expression when they are treated to their very own illegal platter (belly laughs ahoy!)

Also, I finally found a copy of

The Stranglers’ bootleg mentioned above (London

Ladies) and it is a good 'un.

Recorded at the Roundhouse in late 1977, it is far superior to the

official hodgepodge Live (X Cert) and

I’m still kicking myself for not having the money to buy the bugger on that

fateful day.

Also, I finally found a copy of

The Stranglers’ bootleg mentioned above (London

Ladies) and it is a good 'un.

Recorded at the Roundhouse in late 1977, it is far superior to the

official hodgepodge Live (X Cert) and

I’m still kicking myself for not having the money to buy the bugger on that

fateful day.